“My friend who teaches writing sometimes flips out when she is grading stories and types the same thing over and over again. WHERE ARE WE IN TIME AND SPACE? WHERE ARE WE IN TIME AND SPACE?” - Jenny Offill, Department of Speculation

Last week I gave a talk on place and setting for The Faber Academy’s Writing for YA course, and thought I’d put some notes down here.

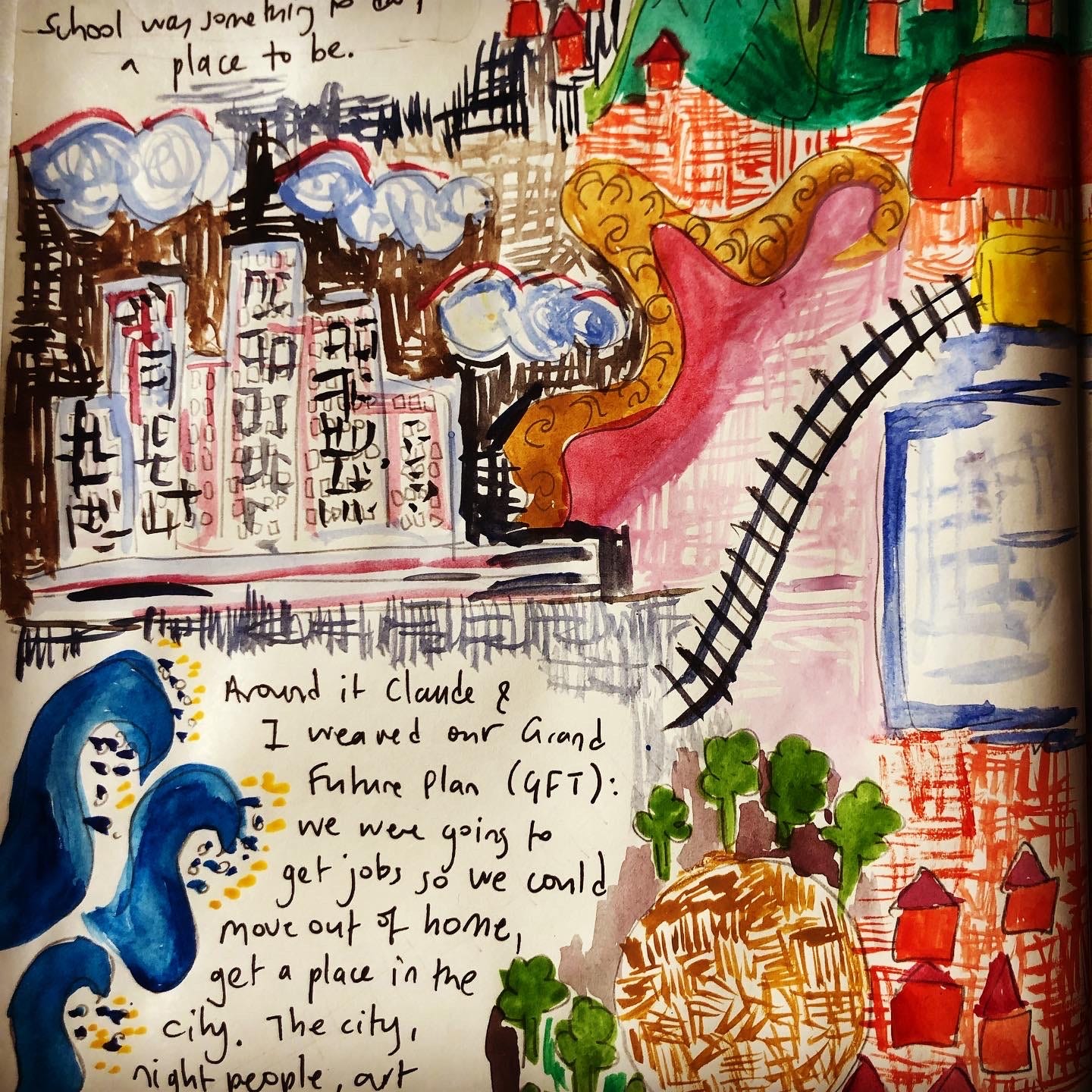

The above picture is a map of the ‘world’ of my first novel ‘Notes from the Teenage Underground’. As you can see, it’s pretty spare. In early drafts it was hardly a world, just a few locations. When I started writing Notes I was living in the UK, and homesick. How many creative works are a result of homesickness I wonder? I had a place in mind, a bushy bucolic suburb not far from where I grew up. A place we used swim at as kids, a place where artists lived, one of those sites of childhood that end up a bit mythic. But as far as other places in the novel went, I didn’t really know them in any material sense. They were vague: the high school grounds after hours, the youth centre, random houses. One of the editorial suggestions was that it could use more detailed descriptions of setting. The editor highlighted places in the novel where I had convincingly ‘sold’ the place and other locations that needed zhooshing, or, even in some cases, actually locating. This was likely the start of me consciously thinking about how place can work for story, how it can be more than just where a story is set, or ‘where stuff happens’; it can also work as prompt or even participant.

PLACE & CHARACTER

Artist Alan Gussow defines place as “a piece of environment that has been claimed by feelings. We are homesick for places … and the catalyst that converts any physical location into a place is the process of experiencing deeply.”

Now, when I am creating a character, I am always thinking about HOW they feel about the places in their world. I try and write in scenes, although it doesn’t always work out that way. Like Jenny Offill’s frustrated teacher writes: “Where are we in Time and Space?”

Jennifer Egan:

“Place is essential to my writing process; my portal into whatever story I’m working on, whether short or long, is almost always a sense of WHERE it starts (and to some degree when). I begin with just that—a sense of atmosphere—and the question of who is perceiving that place comes next, and is a first suggestion of character. Sometimes the place I’m remembering isn’t real; when I wrote The Keep, a gothic thriller, I was remembering an imaginary place—the gothic— familiar to me from books and TV shows and movies.”

Once you have an idea of your character’s places are, you can ask questions like:

Is my character at odds with their environment? (Think, fish out of water narratives - boarding school narratives - stranger in a strange land narratives - folk horror naratives - any fiction where a person has to adjust to new place where everyone knows the the unwritten rules)

Can place help reveal something important about who they are?

If others enter this place, what changes?

BELONGING/UNBELONGING - PUBLIC/PRIVATE

Questions of belonging/unbelonging are so important to YA narratives. One research paper that has informed my thinking is The Unacceptable Flaneur - The Shopping Mall as Teenage Hangout (H. Matthews, M. Taylor, B. Percy-Smith, M. Limb, 1987)

You can find a PDF here.

“On the street teens gather to be and to belong, but it’s a temporary space ‘won out’ from the fabric of adult society and in constant threat of being reclaimed.”

This paper relates Homi Bhaba’s concept of Hybridity to teens in public spaces.

“Hybridity is about how you survive, how you try to produce a sense of agency or identity in situations in which you are continually having to deal with the symbols of power and authority” In the context of the street - or the shopping mall - the teenager is the oppressed figure, taking action via occupation, fighting for their right to exist in the adult world.”

In a shopping centre you can hang out, be visible, perform, interact with your surroundings, you can feel a degree of safety because there is partial supervision, even if that supervision is someone looking on negatively and waiting for you to trip up. Public spaces can be like theatres for human behaviour. They offer opportunities for play - but also, because they’re public the environment can’t be controlled, and that can throw up some interesting possibilities.

And then there are places of refuge.

Where does your character go to be and to belong?

Places of refuge serve important narrative functions - often their introduction pulls focus on a particular friendship, away from the “adult gaze”, they can be sites of transformation or nests for rebellion. In such places, secrets are told, rituals are enacted, things happen that can’t un-happen. They are magic in their possibility, but often they are temporary/doomed.

I have a maybe theory that in a YA novel the destruction or discovery of a character’s place of refuge signifies an acceleration into adulthood/crisis. And just as I write this I remember Badlands, a film I often think about and the bit where Sissy Spacek and Martin Sheen, lovers on the run, live in a treehouse for a while and dance to Love is Strange. This scene is their last moment of utopia before the film barrels down to its bloody end.

PLACE AS WITNESS

Something else I think about is Place as Character/Witness/Commentator. You can find great examples of this in:

A.S King’s Please Ignore Vera Dietz, where The Pagoda, a landmark, gets the odd interstitial moment to share its POV on the story.

(Terrific interview with A.S. King by Danielle Binks here)

Max Porter tackles deep time in Lanny with Dead Papa Toothwort, a ‘Green Man’-esque mythical/folkloric beast who is as old as time and who watches and comments on and directs aspects of the story.

Lanny also features sections where there is a ‘chorus’ voice - random snippets of townsfolk conversation - at the pub, on the street - all fragments that when put together become a masterful evocation of place.

Hayley Scrivenor’s Dirt Town- also features a “WE” voice, in this case a group of school children. “‘Dirt Town’ is a nickname these local kids give Durton, and it felt like a fitting title because for me, the book is about that place they share, the location where their childhood unfolds.”

Another great example of the ‘WE’ is ‘Our Lady of the Quarry’ by Mariana Enriquez: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/12/21/our-lady-of-the-quarry

MAKE A MAP!

Making a map of the places in your novel is a great way to understand spacial awareness, pace and plotting. Assigning places can generate story; following a character through the places of their days can reveal gaps and inconsistencies. If you’re writing about a real place go there often and take field notes. If you’re writing about a made-up place think about what might be your model and go there. Think about landmarks. Think about emotional sacred sites.

I often find drawing helps bring things to life in my mind. It’s like talking something through. You could also create a memory map of your own when your were the age of the character you’re writing about, see what comes up for you.

Remember to create a key/legend - make your own symbols!

Below is made-much-later map for a novel that’s currently sitting in a draw waiting to be dusted off again.